Blog post written by Marta Shocket.

Last month my friend and lab mate Meghan Howard gave a talk at a global health conference and got one of those questions: a question not directly related to her research, but fundamental, big, and interesting. The kind of question that you might hear from a civilian (non-scientist) friend or a relative around the Thanksgiving table.

The question was: How important are mosquitoes for ecosystems? What, if any, calamities would befall the Earth if we could somehow engineer their disappearance? Meghan was quick on her feet and gave a great answer (1). However, our whole lab was having the same nervous reaction in the audience: we knew it was a question that she hadn’t prepared for, and none of us were quite sure how we would answer it in her place. Discussing her improvised answer over lunch, we decided that at our next open lab meeting we would split into teams and tackle popular topics in vector biology. That way, the next time one of us was in the hot seat, we’d be more prepared.

Even though the question about the ecological importance of mosquitoes caught me off guard, it wasn’t a new question for me. I’d been interested enough to bookmark some popular science articles on that exact topic—but of course, not enough to actually read them.

Since others in the vector ecology community might be in a similar boat, this entry will be the first of three blog posts covering the topics we researched for our lab meeting: the role of mosquitoes in ecosystem functioning, Wolbachia bioengineering, and other types of vector bioengineering. Each post will have a short summary of the topic, links to popular and scientific articles if you want to dig deeper, and hopefully some fun and unexpected facts (including the one behind this post’s click-bait title).

So, how important are mosquitoes? The general consensus among scientists is that with a few exceptions, mosquitoes are not very important for ecosystem functioning. Many animals eat mosquitoes, but they only comprise a significant proportion of biomass in the arctic tundra. The migratory birds that breed there would definitely miss them as a food source if they disappeared (2,3). Little Forest Bats in Australia also depend mostly on adult mosquitoes for food (3), and larval mosquitoes are a critical food source for mosquitofish. Beyond these three examples, most other predators are probably generalist enough that they could subsist on other prey items (2).

Aside from being eaten (and of course, transmitting pathogens), mosquitoes have a couple other minor roles. Many mosquito species eat nectar, and some plants rely on them for pollination (2,3). Larval mosquitoes are important for structuring the communities of protists that live inside pitcher plants, and for recycling nutrients to make them available to the plants (2).

However, the most sensational use for mosquitoes was one I found in a relatively obscure article reviewing the potential use of spiders as biocontrol (4). They referenced a study showing that Evarcha culicivora, an East African jumping spider, specifically targets blood-fed Anopheles mosquitoes over sugar-fed ones. The reason for this preference: eating blood-fed mosquitoes gives both males and females a scent that makes them more sexually attractive to mates (5). Not exactly earth-shattering in terms of ecosystem services, but it definitely makes a salacious blog title, and could spice up next year’s conversation around the Thanksgiving table.

A caveat to end: magically disappearing all mosquitoes is an interesting thought-experiment, but not very realistic. The biotech strategies being developed to drive down mosquito populations all target single species that spread infections to humans. These villains account for a tiny proportion of the 3,500 described species of mosquitoes, so the mosquitofish and pitcher plants don’t need to worry too much.

Sources:

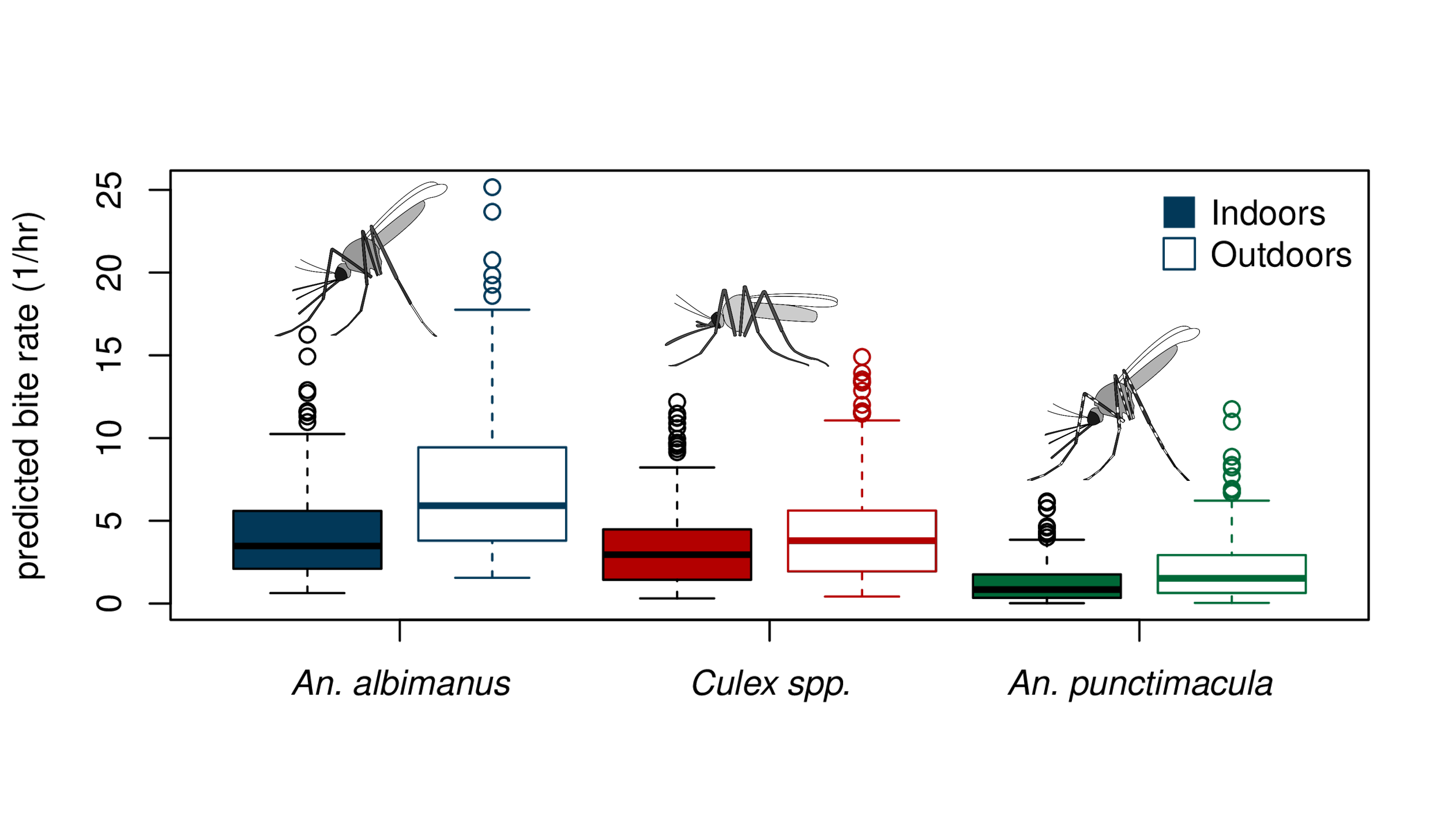

(1) You can watch her talk about mosquito communities across a land use gradient in Costa Rica on youtube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=38xcapLLB7s>. The question in question occurs at around 12:22.

(2) https://www.nature.com/news/2010/100721/full/466432a.html

(3) https://theconversation.com/why-dont-we-wipe-mosquitoes-off-the-face-of-the-earth-54005

(4) http://www.dipterajournal.com/pdf/2018/vol5issue1/PartA/4-6-15-487.pdf

(5) Jackson RR, Cross FR. Mosquito-terminator spiders and the meaning of predatory specialization. Journal of Arachnology. 2015; 43:123-142. PDF

Marta Schocket is a post-doc in the Mordecai lab at Stanford University and a member of VectorBite.